Anyone who has been motivated to read economics for the very first time by the economic crisis that began in 2007 should have realized at least one thing: that communication between economists resembles the Tower of Babel after the confounding of tongues. Economists who speak in one tongue hear what those in another say, but completely fail to understand it—and then shout back something that is just as incomprehensible to the others’ ears.

So I happily doff my cap here to Nick Rowe, who contributes to the “Worthwhile Canadian Initiative” blog, for taking us from the Tower of Babel to the Rosetta Stone. In a blog post entitled “What Steve Keen is maybe trying to say”, he very accurately translated what I have been saying about the role of private debt in aggregate demand into language that Neoclassical economists can understand.

In fact, Nick did better than that: my argument is regularly accused of violating accounting identities, and Nick showed that—as he formulated it—my argument respected accounting identities.

My argument—which I’ll state here in its untranslated form, subject to all the usual criticisms of double-counting and violating accounting identities—is that effective demand is the sum of income plus the change in debt. The conventional case—which is accepted across several economic tongues, including many in the Post Keynesian school with which I’m normally associated—is that aggregate demand is aggregate income, and debt doesn’t come into it. My approach leads me to expect significant causal relationships between changes in private debt and the level of economic activity. Neoclassical economists, on the other hand, generally argue that changes in private debt amount to “pure redistributions [which] should have no significant macro-economic effects…” (Bernanke 2000, p. 24)

Nick’s translation of my argument was as follows:

Aggregate actual nominal income equals aggregate expected nominal income plus amount of new money created by the banking system minus increase in the stock of money demanded.

Nothing in the above violates any national income accounting identity.

As I commented on Nick’s blog, I’m 100% happy with this translation. Nick continued with a story of agent behaviors and expectations to explain his translation:

Here’s the intuition:

Start with aggregate planned and actual and expected income and expenditure all equal. Now suppose that something changes, and every individual plans to borrow an extra $100 from the banking system and spend that extra $100 during the coming month. He does not plan to hold that extra $100 in his chequing account at the end of the month (the quantity of money demanded is unchanged, in other words). And suppose that the banking system lends an extra $100 to every individual and does this by creating $100 more money. The individuals are borrowing $100 because they plan to spend $100 more than they expect to earn during the coming month.

Now if the average individual knew that every other individual was also planning to borrow and spend an extra $100, and could put two and two together and figure out that this would mean his own income would rise by $100, he would immediately revise his plans on how much to borrow and spend. Under full information and fully rational expectations we couldn’t have aggregate planned expenditure different from aggregate expected income for the same coming month.

But maybe the average individual does not know that every other individual is doing the same thing. Or maybe he does know this, but thinks their extra expenditure will increase someone else’s income and not his. Aggregate expected income, which is what we are talking about here, is not the same as expected aggregate income. The first aggregates across individuals’ expectations of their own incomes; the second is (someone’s) expectation of aggregate income. It would be perfectly possible to build a model in which individuals face a Lucasian signal-processing problem and cannot distinguish aggregate/nominal from individual-specific/real shocks.

So at the end of the month the average individual is surprised to discover that his income was $100 more than he expected it to be, and that he has $100 more in his chequing account than he expected to have and planned to have. This means the actual quantity of money is $100 greater than the quantity of money demanded. And next month he will revise his plans and expectations because of this surprise. How he revises his plans and expectations will depend on whether he thinks this is a temporary or a permanent shock, which has its own signal-processing problem. And these revised plans may create more surprises the following month.

Nick also realized something which is quite crucial: that this is an argument about an economy in disequilibrium:

We are talking about a Hayekian process in which individuals’ plans and expectations are mutually inconsistent in aggregate. We are talking about a disequilibrium process in which people’s plans and expectations get revised in the light of the surprises that occur because of that mutual inconsistency.

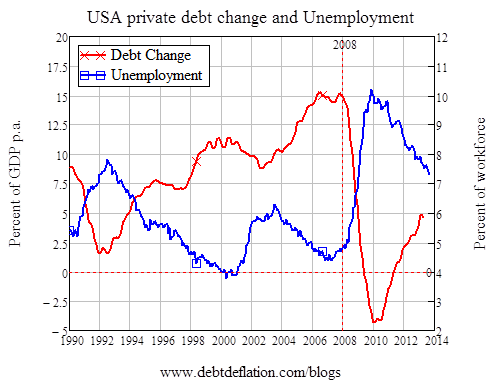

Nick’s translation of my argument into terms that Neoclassical economists (and accountants) can understand could lead to some significant changes in economics from that school. Certainly, it provides a way to interpret phenomena like those highlighted in Figure 1—the extremely high correlation between changes in private debt and the level of economic activity—which are otherwise anomalies if changes in debt are “pure redistributions” as Bernanke argued.

Figure 1: Change in private debt & unemployment–correlation ‑0.9

This may be difficult to achieve, since as Nick noted this is a disequilibrium argument, and Neoclassical economics is traditionally couched in terms of equilibrium processes. But I certainly hope that it does lead to a changed appreciation of the role of banks, debt and money in Neoclassical economics. After all, it’s progress towards realism that matters in economics, far more so than who achieves it.

I’ll close by thanking Nick once more for moving us further down the path towards realism, and away from Babel.

Shortly I’ll provide a follow-up to Nick’s post that puts the argument about the role of change in debt in effective demand into mathematical form. Warning—it will definitely qualify for an “extra-super-wonkish” award.

Bernanke BS. 2000. Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton: Princeton University Press.