I was asked to contribute to an Italian online publication’s tribute to John Kenneth Galbraith, by answering some questions about the relevance of his major work The New Industrial State (Galbraith and Galbraith 1967) six decades later. These were my responses.

About sixty years later, how relevant and actual is the vision of the American economy and economic system proposed by John K. Galbraith in his “The new industrial state”?

Reading The New Industrial State (Galbraith and Galbraith 1967) again, six decades after it was first published, highlighted for me just how far economic theory has retreated from reality since the 1960s.

The New Industrial State (hereinafter called TNIS) described the actual structure of a modern industrial economy. It has nothing to do with Alfred Marshall’s vision of a market economy, in which a multitude of small entrepreneurial firms sold homogenous goods directly to consumers in anonymous markets, and in which prices were set by the intersection of supply and demand. Instead, the economy is dominated by large corporations, which themselves are run by a bureaucratic “technostructure”—the term Galbraith invented—that attempts to manage everything, from input costs to final consumer demand which they manipulate via marketing. Prices are tamed by long term contracts, and the only source of instability in prices comes from wage demands on the one hand, and the vagaries of agricultural and energy production on the other.

This was the reality of the mid-1960s on which Galbraith commented. At the time he wrote, Galbraith was confident that this reality would supplant the Marshallian fantasy of supply and demand curves, which dominated economic theory.

Fat chance! Galbraith’s optimism about his profession of economics was misplaced: faced with a conflict between reality and theory, mainstream economic elevated theory over the inconvenient facts of the real world. The main real-world changes since Galbraith’s time have been the crushing of trade unions, which has largely eliminated the capacity of workers to bargain for wage rises, the development of globalization, which has created long and extremely fragile supply chains, with much production occurring offshore rather than in American factories, and the financialization of near everything. But a “technostructure” is still in charge, and the realities of production, management and marketing are the same as he observed in the mid-1960s.

None of this realism has seeped into economic theory.

Galbraith gained his knowledge of the actual nature of the management of industrial capitalism from simple observation and, crucially, being involved in the procurement and price control efforts of World War II. In the 1990s, the mainstream economist Alan Blinder gained similar knowledge via a very careful random survey of American companies with sales exceeding $10 million per year.

The answers these companies gave Blinder about their operations turned everything in mainstream economics upside-down—just as Galbraith’s book had done 30 years earlier. Firms face falling marginal costs, not the rising marginal costs assumed by economic theory. Over 70% of their output is sold to other companies, not to end consumers. Prices of industrial goods are subject to long-term contracts, and change rarely. Word for word, the survey reproduced the vision of the corporate sector that Galbraith had laid out. Blinder himself observed that “The overwhelmingly bad news here (for economic theory) is that, apparently, only 11 percent of GDP is produced under conditions of rising marginal cost”, and that “their answers paint an image of the cost structure of the typical firm that is very different from the one immortalized in textbooks” (Blinder 1998, pp. 102, 105).

The real world is “overwhelmingly bad news” for economic theory because, with falling marginal cost, the textbook supply curve does not exist: the output of firms is not constrained by rising costs, but instead, any firm that secures a larger market share also secures a higher profit. The neat equilibrium of the textbook is replaced by an evolutionary struggle for survival and dominance.

Not a word of that reality made it into economic textbooks. Even Blinder’s own undergraduate textbook (Baumol and Blinder 2015) pretends that Marshall’s model is accurate, despite his own knowledge that the results of his survey were “overwhelmingly bad news here (for economic theory)”.

Galbraith’s book therefore remains relevant as a description of economic reality, but the optimism he had that his realistic vision would replace textbook fantasies was misplaced.

Do you think that today we have passed from an industrial technostructure to a digital and high tech technostructure? Has the role, once of the industrial circuit, been taken today by big tech and corporate related to social networks?

Much of the US industrial circuit has been relocated to China and other developing economies, but if anything this has strengthened the importance of the technostructure: the coordination that Galbraith saw playing out across the continental USA is now an order of magnitude more complex.

The growth of software has also made Galbraith’s analysis even more apposite. Though the marginal costs of industrial firms are low and falling—the opposite of the textbook model—the marginal costs of software firms are closer to zero. The profit margins from market dominance are therefore even bigger. There is no second place in the word processor market (Microsoft Word) or the browser market (Google Chrome), and second place in the operating system market (Apple MacOs) is long distant from first place (Windows).

The need to control prices and manage demand are even bigger in the digital/high-tech world than they were in Galbraith’s industrial day, while the capacity for market dominance by the market leader is stronger still where products have a substantial network effect. This applies to everything from the obvious—such as social media products like Twitter and Facebook—to the mundane. Word’s dominance of the word processor market is largely due to the fact that it was the program most users used. Minority product users—which I once was, using Lotus Word Pro in preference to Word because of its superior desktop publishing features—were forced to adopt Word for compatibility with the people with whom we had to communicate. Rivals like Word Pro withered and died in the marketplace, simply because they were not the number one product.

Textbooks treat this as an interesting—and easily ignored—exception to the assumed rule of rising marginal cost. But in fact, it is an amplification of the processes Galbraith identified in the industrial state, which make the textbook model even more irrelevant to the real world.

Is the role of the proletariat and the workforce in this new digital state today played by capital and technical means that replace the social weight of the workforce?

The decline in the political power of the working class since the publication of TNIS has been dramatic. Galbraith foresaw this possibility, as he noted the extent to which the technostructure attempted to have workers identify with the firm rather than their social class. Here Galbraith deserves praise for a great deal of prescience:

The planning system, it seems clear, is unfavorable to the union. Power passes to the technostructure, and this lessens the conflict of interest between employer and employee which gave the union much of its reason for existence. Capital and technology allow the firm to substitute white-collar workers and machines that cannot be organized for blue-collar workers who can. The regulation of aggregate demand, the resulting high level of employment together with the general increase in well-being, all, on balance, make the union less necessary or less powerful or both. The conclusion seems inevitable.

The union belongs to a particular stage in the development of the planning system. When that stage passes, so does the union in anything like its original position of power. And, as an added touch of paradox, things for which the unions fought vigorously—the regulation of aggregate demand to ensure full employment and higher real income for members—have contributed to their decline. (Galbraith and Galbraith 1967, p. 337)

Starting from the text “The economy of innocent fraud” how has the role of finance changed the link between technostructure and markets?

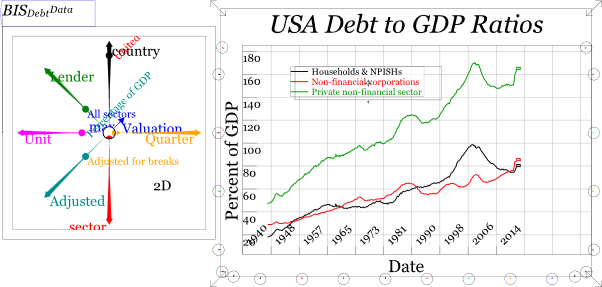

One factor that Galbraith did not anticipate in 1967 was the rise in the significance of the financial sector, not only in the USA, but worldwide. When TNIS was published, private debt was under 90 percent of GDP, and the industrial sector was the dominant sector of the US economy. Today, private debt is over twice as high relative to GDP, and the financial tail now wags the industrial dog—see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Private debt is dramatically higher today than it was when TNIS was first published in 1967

As a result, America is no longer dominated by the military-industrial complex—to use the phrase invented not by Galbraith, but his contemporary President Dwight D. Eisenhower—but by what I call the politico-financial complex. We have to look, not to Galbraith in 1967, but to Marx a century earlier, for an accurate characterisation of what this has meant for the viability of the capitalist system:

Talk about centralisation! The credit system, which has its focus in the so-called national banks and the big money-lenders and usurers surrounding them, constitutes enormous centralisation, and gives to this class of parasites the fabulous power, not only to periodically despoil industrial capitalists, but also to interfere in actual production in a most dangerous manner—and this gang knows nothing about production and has nothing to do with it. (Marx 1894, Chapter 33)

What is the major legacy of Galbraith?

Re-reading TNIS made me nostalgic for the 1960s, not because the music was better—though, of course, it was—but because the vision of the future which Galbraith had was better than the future itself has turned out to be. Galbraith’s erudite prose was underwritten by a presumption that the knowledge he had acquired—of how the American industrial sector actually functioned—would supplant the reassuring fictions of Marshallian markets that academic economists continued to peddle in their first year textbooks.

It didn’t. Economic textbooks today are even more arcane than the academic products of the 1960s, which Galbraith felt he could comfortably disparage as he outlined what he called the “revised sequence” of how goods are manufactured and marketed in an advanced capitalist economy:

In the form just presented, the revised sequence will not, I think, be challenged by many economists. There is a certain difficulty in escaping from the inescapable. There is more danger that the point will be conceded, and its significance then ignored…

The revised sequence sends to the museum of obsolete ideas the notion of an equilibrium in consumer outlays which reflects the maximum of consumer satisfaction. (Galbraith and Galbraith 1967, p. 265)

Unfortunately, his “revised sequence” was not even conceded by the discipline, let alone ignored. The museum of obsolete ideas is alive and well in the 2020s, instructing economics students today in a vision of a market economy even more arcane that the 1960s economics textbooks that Galbraith clearly—and wrongly—thought were going the way of the Dodo.

Instead, Galbraith’s own contributions largely went the way of the Dodo. Modern students of economics are unaware of his contributions, from the practical work he undertook to enable the USA to dramatically expand wartime production without causing inflation in either military or consumer goods prices, to his eloquent erudition of an alternative economics in works such as TNIS, The Affluent Society (Galbraith 2010) and The Great Crash 1929 (Galbraith 1955).

Galbraith partly contributed to his own subsequent irrelevance, by not providing a means by which his eloquence could be turned into equations. His contemporary Hyman Minsky (Minsky 1975, 1982), who was far less well-known than Galbraith at the time—even in non-orthodox economic circles—is the one whose non-orthodox vision lives on after him, largely because his vision could be put into a range of analytic forms (Keen 1995; Delli Gatti and Gallegati 1996; Dymski 1997; Wray 2010; Keen 2020). Even Neoclassicals, who remain as ignorant of Minsky’s real insights as they are of Galbraith’s, must acknowledge the existence of “Minsky Moments” (Bressler 2021). There is no Galbraithian equivalent.

6) What would be the characteristics of a “New Digital state”?

The main difference between the Industrial State that Galbraith described, and the Digital (and Financial) State in which we reside today is the importance of network effects for the Digital economy.

The goods produced by the companies Galbraith’s that treatise considered were not dependent on widespread consumer conformity. The New Industrial State led to the dominance of mega-corporations (like Ford, General Electric, and IBM), but their dominance did not mean that rival companies (like General Motors, Westinghouse and Burroughs) were unable to achieve market share. However, in today’s Digital State, it is near impossible for a rival to Facebook to achieve critical mass, because Facebook already has that critical mass. This makes the Digital State a much more all-or-nothing contest than the New Industrial State of the mid-1960s.

The effect is profound. If the market had reason to complain about the product of an industrial giant—say, for example, the Ford Edsel—it was easy to switch to a rival product from a rival manufacturer. But complain as consumers do today about Google, Facebook and Twitter, the capacity to turn those complaints into a rival product is virtually non-existent.

In this way, the dominance of the technostructure over the market that Galbraith identified in the 1960s is even greater today. But the Silicon Valley hipsters who might well use the word as they debate the Internet-Of-Things over a soy latte would never know that the word that describes them so well was invented by John Kenneth Galbraith.

Baumol, William J, and Alan S Blinder. 2015. Microeconomics: Principles and policy (Nelson Education).

Blinder, Alan S. 1998. Asking about prices: a new approach to understanding price stickiness (Russell Sage Foundation: New York).

Bressler, Paige D. 2021. ‘In a Minsky Moment, can financial statement data predict stock market crashes and recessions?’, The Journal of corporate accounting & finance, 32: 155–63.

Delli Gatti, Domenico, and Mauro Gallegati. 1996. ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis and Stabilization Policy: Hyman P. Minsky’s Contribution to Political Economy’, Economic Notes, 25: 411–24.

Dymski, Gary. 1997. ‘Deciphering Minsky’s Wall Street Paradigm’, Journal of Economic Issues, 31: 501.

Galbraith, James K. 2010. The affluent society and other writings, 1952–1967 (Penguin: New York).

Galbraith, John Kenneth, and James K. Galbraith. 1967. The new industrial state (The James Madison library in American politics) (Princeton University Press: Princeton).

Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1955. The Great Crash 1929 (Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston.).

Keen, Steve. 1995. ‘Finance and Economic Breakdown: Modeling Minsky’s ‘Financial Instability Hypothesis.”, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 17: 607–35.

———. 2020. ‘Emergent Macroeconomics: Deriving Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis Directly from Macroeconomic Definitions’, Review of Political Economy, 32.

Marx, Karl. 1894. Capital Volume III (International Publishers: Moscow).

Minsky, Hyman P. 1975. John Maynard Keynes (Columbia University Press: New York).

———. 1982. Can “it” happen again? : essays on instability and finance (M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, N.Y.).

Wray, L. Randall. 2010. ‘Minsky, the Global Money-Manager Crisis, and the Return of Big Government.’ in Steven Kates (ed.), Macroeconomic Theory and Its Failings: Alternative Perspectives on the Global Financial Crisis (Cheltenham, U.K. and Northampton, Mass.: Elgar).