This is an invited paper by the Private Debt Project, an initiative of the philanthropic organization the Governor’s Woods Foundation to raise awareness about the economic importance and dangers of private debt.

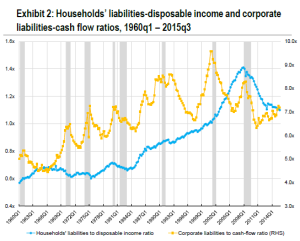

The era of low growth known as Japan’s “Lost Decade” commenced in 1990, and persists to this day. While most authors acknowledge that the seeds for the Lost Decade were sown by excessive credit growth in the preceding Bubble Economy years, only Richard Koo (Koo, 2009, Koo, 2011, Koo, 2003, Koo, 2014) and Richard Werner (Voutsinas and Werner, 2011, Werner, 2002) have systematically argued that insufficient credit growth during the “Lost Decade” explains Japan’s now quarter-century long slump. Yet these arguments tell us more about the dilemmas facing today’s world economy than many more commonly accepted explanations of the current slowdown.