I was recently informed that a Spanish translation of Debunking Economics is now available via Amazon Spain, under the title “La Economía Desenmascarada”

There’s one review so far:

I was recently informed that a Spanish translation of Debunking Economics is now available via Amazon Spain, under the title “La Economía Desenmascarada”

There’s one review so far:

The mainstream economic idea that banks are just intermediaries between savers and investors is a fantasy, but given that fantasy, their argument that the level and rate of change of private debt are not macroeconomically significant (except at the “Zero Lower Bound”) is correct. But in the real world, the role of the level and rate of change of private debt is crucial. I illustrate this by building a Minsky model of Loanable Funds and converting it to the real world of Endogenous Money. Then I explain how credit growth plays an essential role in aggregate demand and income, and how this is consistent with the truism that Expenditure equals Income.

Like many commentators, I regard August 9 2007 as the start of the “Global Financial Crisis”. On that day, BNP Paribas declared that several of its funds were being closed because liquidity in those markets had completely evaporated:

So I was particularly amused–in a sick sort of way–to see this brilliant info-graphic on The Fed on Twitter today: it plots the amount of laughter in FOMC meetings between 2000 and 2012. “Peak Laughter” occurred literally days before the crisis began:

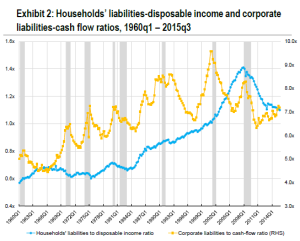

PERG economists are developing a macroeconometric model to track the evolution of the US economy over the medium term, which is 3–5 years:

The model belongs to the family of “financial balances models”, an approach pioneered by Wynne Godley and collaborators at Cambridge University (UK) and then successfully developed by the macroeconomics team of the Levy Institute — led by Godley himself.

At its heart, the KFBM (Kingston Financial Balances Model) is characterised by a set of thorough accounting matrices that gather the major stocks and flows of the US economy as well as their links across institutional sectors. This results in three key strengths of the KFBM:

As I explained in my last post, banks can’t “lend out reserves” under any circumstances, which undermines a major rationale that Central Bank economists gave for undertaking Quantitative Easing in the first place. Consequently, the hope that Bernanke expressed in 2009 is “To Dream The Impossible Dream”:

To dream the impossible dream

To fight the unbeatable foe

To bear with unbearable sorrow

To run where the brave dare not go

Former Chair of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke listens while US Secretary of the Treasury Jacob Lew speaks at the Brookings Institution July 8, 2015 in Washington, DC. AFP PHOTO/BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI (Photo credit should read BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty Images)

I began another post critical of Joe Stiglitz’s analysis with the caveat that I like Joe. I’ll add to that that I respect his intellect too, both because he’s very bright—you don’t win a Nobel Prize (even in Economics!) without being very bright—and because compared to some other winners, he is very capable of thinking beyond the limitations of the mainstream.

But there are some mainstream concepts that are so deeply embedded in even highly intelligent, flexible thinkers like Joe, that they continue thinking in terms of them, when a bit of really serious thought would show that the concepts are in fact nonsense.

The great tragedy of the global economic malaise is that it is caused by a shortage of something that is essentially costless to produce: money.

I’m posting videos of lectures given by my Kingston colleagues to the introductory “Becoming an Economist” course, since the StudySpace software Kingston uses doesn’t support MP4 files. The first is Devrim Yilmaz’s lecture last week on “Data Collection and Presentation”.

I’ve been Head of School at Kingston University London for over 18 months now, but these things do take time: last Wednesday I gave my inaugural Professorial lecture to an audience of about 200 people. My screen-recording video of the talk is below. Click here to download the Powerpoint slides; Minsky crisis model; Minsky Loanable Funds model; Minsky Endogenous Money model; Private Debt levels (6 countries); Private Credit growth (6 countries); USA Private Debt change & Unemployment; Private Debt Acceleration & Asset Prices.

I like Joe Stiglitz, both professionally and personally. His Globalization and its Discontents was virtually the only work by a Nobel Laureate economist that I cited favourably in my Debunking Economics, because he had the courage to challenge the professional orthodoxy on the “Washington Consensus”. Far more than most in the economics mainstream—like Ken Rogoff for example—Joe is capable of thinking outside its box.

But Joe’s latest public contribution—“The Great Malaise Continues” on Project Syndicate—simply echoes the mainstream on a crucial point that explains why the US economy is at stall speed, which the mainstream simply doesn’t get.