By Philip Pilkington, a writer and journalist based in Dublin, Ireland. You can follow him on Twitter at @pilkingtonphil

The so-called ‘market monetarists’ – that is, a growing pack of neoclassical economists who are advocating that central banks should try to generate inflation – are not as strange a breed as many think. Recently we compared classic deflationary monetarism with contemporary QE policies and found that they were based on the same underlying theoretical framework. We also found that the high priest of classical monetarism himself, Milton Friedman, strongly advocated inflationary monetary policies for both Japan after 1991 and the US after the stock market crash of 1929. So, it is by no means surprising that when one monetarist policy fails (I refer to QE), another will quickly be cooked up by Friedman devotees.

monetarists’ – that is, a growing pack of neoclassical economists who are advocating that central banks should try to generate inflation – are not as strange a breed as many think. Recently we compared classic deflationary monetarism with contemporary QE policies and found that they were based on the same underlying theoretical framework. We also found that the high priest of classical monetarism himself, Milton Friedman, strongly advocated inflationary monetary policies for both Japan after 1991 and the US after the stock market crash of 1929. So, it is by no means surprising that when one monetarist policy fails (I refer to QE), another will quickly be cooked up by Friedman devotees.

That is precisely the role of the market monetarists in the current policy and economic debates. They have introduced the banal notion that central banks should no longer target inflation or unemployment but instead they should focus on Nominal Gross Domestic Product (NGDP) – that is, a measure of GDP that has not been adjusted for inflation. The idea is that the central banks should pump up non-inflation adjusted GDP until economic growth begins once more.

begins once more.

The only thing that market monetarists are more vague on than how such inflation will translate into economic growth (money supply voodoo?) is how they will actually accomplish the NGDP targets. Sometimes they refer to devaluation, sometimes to inflationary expectations, sometimes to banks levying taxes on deposits, sometimes… wait for it… to more QE – indeed, one sometimes gets the impression that they are saying nothing new at all. However, we will not concern ourselves here with peering into their little black boxes. Instead we will focus on what might, in the unlikely event that they succeed in their policy goals, be the likely end result. But first a detour into the distribution of income in today’s US of A.

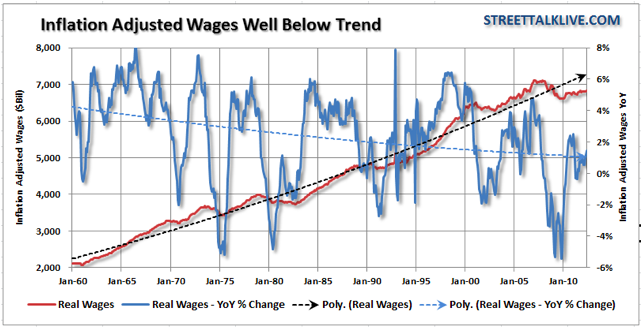

Recently Lance Roberts ran an excellent piece on corporate profitability and wages. He showed that while corporate profits are rising, real worker incomes are falling below trend. He provides the following graph to illustrate this:

Looking into this trend, Roberts notes that it is mainly due to changes in the structure of the US labour market. He is worth quoting in full in this regard:

The single biggest expense to any company is full-time employees: payroll, taxes and benefits. While the economy has grown since the depths of the last recession, demand has remained weak in terms of sales growth. The lack of demand has kept businesses on the defensive with a focus on maximizing profitability of each dollar of revenue. During the recession, and recovery, businesses have kept very tight controls on costs by reducing inventory levels, cutting budgets and maximizing productivity per employee. This has also led to massive changes in hiring and employment. Temporary hires (which have lower wages and no benefit costs) have substantially outpaced permanent employment since the end of the last recession. Since the first quarter of 2009, part-time employment has increased by more than 1.5 million while full-time employment is still lower by 1.25 million. The analysts and media have been quick to jump on the idea that temporary jobs will ultimately turn into full-time employment. However, in an economy that is growing at a sub-par rate with a large and available labor pool, the use of temporary versus full-time employment may well be the “new normal”. This also explains why dependence on “food stamps” have surged by over 14 million participants during the same period.

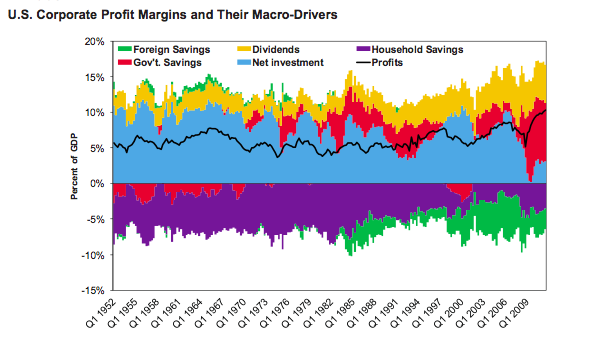

Roberts notes that this is a curious situation because falling real wages should impart a deflationary bias to the economy as a whole due to less people having money to spend on goods and services. Actually this situation is not so curious if we remember the Kalecki profits equation (which we dealt with in depth here). While there are a few iterations the Kalecki equation is best stated as such:

Pn = I + (G – T) + NX + Cp – Sw

Pn = total profits after tax. I = gross investment. G = government spending. T = total taxes. (So, G – T = the total government budget deficit). NX = net exports (total exports minus total imports). Cp = capitalists’ consumption. And Sw = total workers’ saving.

So, in English that equation reads as follows:

Profits – Tax = Gross Investment + Government Deficit + Net Exports + Capitalists’ Consumption – Workers’ Saving

Now, if we follow Roberts and assume that the labour market is being increasingly squeezed we can easily guess where all that extra demand is coming from. It is, of course, coming from two channels – the only two possible channels given the current macroeconomic picture of the US – that is: the government deficit and capitalist consumption (which can be read as: consumption out of previous profits). Of the two of these government deficits are by far the most important.

Indeed, James Montier from GMO [] has crunched the numbers and turned out evidence that confirms exactly what we would intuitively expect – namely that government deficits are the main drivers of profits in the post-2008 world:

Now that we’ve run through some structural distributionary features of the US economy, back to the market monetarists. What does all this mean? Well, it seems that although fiscal deficits by the US government are indeed propping up the economy and ensuring that those that have jobs can continue to remain employed, they are also covering up growing macroeconomic structural imbalances. Because there are such wide deficits and because these support corporate profits, companies have been able to suppress real wage growth and this has not significantly affected demand for their goods and services.

So, if the market monetarists had their way and provoked added inflation in the economy it is clear that this would not necessarily result in real wage growth to match said inflation. The labour market is extremely slack at the moment and, as Roberts has shown above, employers are using this opportunity to supress real wages below trend. If a burst of inflation shot through the system there seems no reason to assume that real wages could keep pace. Much more likely that they would fail to rise and living standards would fall. And as people needed to use more of their income to buy fewer, higher-priced goods and services this would also lead to lower economy-wide demand.

Indeed, such a policy might, if pursued with gusto, lead to a stagflation scenario where workers suffered unemployment on the one hand and falling living standards on the other. What a mess that would be… and, it should be said for those New Keynesians who tie their flag to this mast (you know who you are), it would make it all the more difficult to clear this disaster up with fiscal stimulus and other sensible policy measures as this might feed into the artificially generated inflation.

As we said though, it is unlikely that the market monetarists’ policies will be able to generate inflation even if they are implemented. The last time monetarist cranks got into power their policies were used to mask political aspirations that the general public would not have otherwise accepted. This time around, if the central bank chooses NGDP targeting as its new shaman’s stick – since the QE-wand has by now gone completely and comically floppy – they will likely just fall flat on their face. Where once monetarism was a grim mask worn by a disingenuous reaper intent on mass destruction, today it appears as nothing more than a cockscomb worn by an insecure fool trying desperately to convince the financial markets of his continuing relevance.