Mike Shedlock (“Mish” as he is known to all) has written an excellent piece on the deflation-inflation debate, focusing on the Achilles Heel of the latter–the fact that it is based on the belief that we live in a “fractional reserve banking” monetary system. He offered to let me cross-post here, and I’ve reproduced it in its entirety below (there’s only one point I’m not sure on–the comment that there are no reserve requirements for savings accounts. From my reading of the footnotes to Table 12 in this Federal Reserve paper, that’s true of corporate accounts but not individual ones).

Also, there is an excellent article in the Guardian “The global economy’s decade of debt-fuelled boom and bust” by Larry Elliott (reproduced in the Fairfax press) that puts the debt-deflation and deleveraging case very well. Do read it.

And now, over to Mish!

Fictional Reserve Lending And The Myth Of Excess Reserves

In A Case for the Inflation Camp Robert P. Murphy asks When Will the Inflation Genie Get Out of the Bottle? Murphy’s concern is over “excess reserves”.

My reason for expecting large-scale price inflation is fairly straightforward: I see no coherent strategy for Bernanke to remove the excess reserves from the banking system. …

After reviewing the evidence and the theories offered by the two camps, I still believe that Bernanke’s unprecedented infusions of new reserves will lead to rapid price increases. These increases may not show up in the price of US financial assets, but they will rear their ugly heads at the gas pump and grocery checkout. Moreover, I think the genie may already be slipping out of the bottle. His escape will only be hastened once the year-over-year CPI figures show moderate inflation.

Steve Saville’s Concern Over Excess Reserve

Steve Saville expresses his concern over excess reserves in Bank Reserves and Inflation.

The reason that bank reserves aren’t added to the money supply is that they do not constitute money available to be spent within the economy; rather, they constitute money that could be loaned into the economy or used to support additional bank lending in the future.

Bank lending in the US has declined on a year-over-year basis, so we know that the spectacular increase in reserves has not YET contributed to monetary inflation.

If the private banks were to join the inflation party then the risk of hyperinflation would greatly increase, and hyperinflation — leading to what Mises called a “crack-up boom” — would be the worst of all possible outcomes. In particular, it would be an order of magnitude worse than the deflation that many people still seem to be worried about.

So, let’s hope that the banks don’t start lending out their excess reserves. The situation is bad enough already.

Gary North’s Concern Over Excess Reserves

Inquiring minds note Gary North’s concern over excess reserves in The Federal Reserve’s Self-Imposed Dilemma.

The Federal Reserve System faces a dilemma of its own creation: the doubling of the monetary base.

The only thing that is keeping this from creating mass inflation is the decision of commercial bankers to deposit the bulk of this increase with the Federal Reserve. The banks are not lending out this money. Neither is the FED. This money does not legally belong to the FED.

AN EASY SOLUTION WITH DISASTROUS CONSEQUENCES

There is an easy solution to this problem. The Federal Reserve knows exactly what the solution is. Nobody mentions it. The suggestion that the Federal Reserve would attempt it would probably bust the bond market. The Federal Reserve would announce that, from this point on, all money deposited by banks as excess reserves will be charged a storage fee. This fee could be 2%.

Not only would banks not make any interest on the money deposited with the Federal Reserve, they would begin suffering a loss of 2% per annum on the money held as excess reserves. …

Lots of Concern Over Excess Reserves

That’s a lot of concern over excess reserves. And if I looked around, I am quite sure I can find even more concern over excess reserves.

Here is a current chart that shows what everyone is concerned about.

Reserve Balances with Federal Reserve Banks

click on chart for sharper image

Money Multiplier Theory

The chart shows an unprecedented amount of excess reserves, almost $1.2 trillion.

According to Money Multiplier Theory (MMT) and Fractional Reserve Lending, this amount may be lent out as much as 10 times over and when it does, massive inflation will result.

Money Multiplier Theory Is Wrong

The above hypotheses regarding “Excess Reserves” are wrong for five reasons.

1) Lending comes first and what little reserves there are (if any) come later.

2) There really are no excess reserves.

3) Not only are there no excess reserves, there are essentially no reserves to speak of at all. Indeed, bank reserves are completely “fictional”.

4) Banks are capital constrained not reserve constrained.

5) Banks aren’t lending because there are few credit worthy borrowers worth the risk.

Let’s explore each of those points in depth.

1: Lending Comes First, Reserves Second

Australian economist Steve Keen has made a strong case that lending comes first and reserves later in Roving Cavaliers of Credit. I discussed that at length in Fiat World Mathematical Model.

That point alone should seal the hash of the debate but it keeps coming up over and over. So let’s try one more time.

Inquiring minds are reading BIS Working Papers No 292, Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal.

Note: The above link is a lengthy and complex read, recommended only for those with a good understanding of monetary issues. It is not light reading.

The article addresses two fallacies

Proposition #1: an expansion of bank reserves endows banks with additional resources to extend loans

Proposition #2: There is something uniquely inflationary about bank reserves financing

From the article.…

The underlying premise of the first proposition is that bank reserves are needed for banks to make loans. An extreme version of this view is the text-book notion of a stable money multiplier.

In fact, the level of reserves hardly figures in banks’ lending decisions. The amount of credit outstanding is determined by banks’ willingness to supply loans, based on perceived risk-return trade-offs, and by the demand for those loans.

The main exogenous constraint on the expansion of credit is minimum capital requirements.

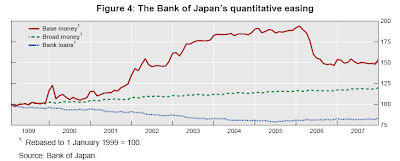

A striking recent illustration of the tenuous link between excess reserves and bank lending is the experience during the Bank of Japan’s “quantitative easing” policy in 2001–2006.

Japan’s Quantitative Easing Experiment

click on chart for sharper image

Despite significant expansions in excess reserve balances, and the associated increase in base money, during the zero-interest rate policy, lending in the Japanese banking system did not increase robustly (Figure 4).

Is financing with bank reserves uniquely inflationary?

If bank reserves do not contribute to additional lending and are close substitutes for short-term government debt, it is hard to see what the origin of the additional inflationary effects could be.

There is much additional discussion in the article but it is clear that MMT theory as espoused by Murphy, Saville, North and others did not happen in Japan nor is there any evidence of it happening in the US, nor is there a sound theoretical basis for it.

In fiat based credit systems, lending comes first, reserves come second, and extra reserves do nothing much except pay banks to sit in cash in cases where interest is paid on excess reserves.

I will touch more on reserves coming after lending in the discussion of points 3 and 4 below.

2: There Are No Excess Reserves

Let’s now turn our attention to the idea there are excess reserves. To do that, let’s consider nonperforming loans, total loans and leases, and allowances for loan and lease losses.

Total Nonperforming Loans

click on chart for sharper image

The above chart is from St. Louis Fed based on Reports of Condition and Income for All Insured U.S. Commercial Banks.

Percentage of nonperforming loans equals total nonperforming loans divided by total loans. Nonperforming loans are those loans that bank managers classify as 90-days or more past due or nonaccrual in the call report.

Nonperforming loans have soared to a record five percent for this series.

The above chart just gives a percent. We need to quantify the amount. The following chart will help do just that.

Total Loans and Leases of Commercial Banks

The above chart of total loans and leases shows a total of nearly $7 trillion, of which five percent is nonperforming. In other words there is about $350 billion of nonperforming loans on the books of banks (that are admitted to).

That last part about admitted to is crucial. Nonperforming loans do not include off balance sheet garbage, various swaps with the Fed, or ridiculous mark-to-fantasy valuations of assets held on the books.

Total Loans and Leases of Commercial Banks Percentage Change

On a percentage basis the drop in loans and leases is unprecedented.

But wait. Banks might have made provisions for those loan losses already, might they not? Well … in a single word, No (as the following chart shows)

Assets at Banks whose ALLL exceeds their Nonperforming Loans

The above chart courtesy of the St. Louis Fed.

Because allowances for loan losses are a direct hit to earnings, and because allowances are at ridiculously low levels, bank earnings (and capitalization ratios) are wildly over-stated.

Excess Reserves? You still think so?

3: Bank reserves are “Fictional”, there are essentially no reserves at all.

To see if we can prove this statement we can look at total lending vs. base money supply and M2.

Karl Denninger at Market Ticker has a nice chart of total lending based on Federal Reserve Z.1 Flow of Funds data.

Cumulative Debt

click on chart for sharper image

Base Money Supply

Note the rampant increase in base money which is the source of those so-called excess reserves.

Let’s do a little math.

There is 2,000 billion base money.

There is 52,000 billion lending.

The ratio of base money to lending is 3.8%

Prior to the ramp in base money (which by the way was the Fed’s feeble attempt to supply reserves after the fact), there was $800 billion base money supporting $52,000 billion in lending. Not too long ago, the ratio of base money to lending was a mere 1.5%.

Want to use M2 instead?

M2 Money Supply

click on chart for sharper image

Using M2 as money supply available for lending makes the ratios better. However, the largest component of M2 is savings accounts at almost $5 trillion of that $8.5 trillion M2.

However, money in savings accounts is not there. Reserve requirements on savings accounts are zero. It has all been lent out. Moreover, Greenspan authorized sweeps in 1994 to specifically allow banks to “sweep excess reserves” from checking accounts into savings accounts so the money could be lent out.

There is no money in savings accounts or checking accounts other than an electronic mark that says there is. Both contain money only in theory. That money that has already been lent out and redeposited, over and over and over.

Reserves? There are no reserves. Indeed, reserves are best thought of as negative.

Fractional Reserve Lending is really Fictional Reserve Lending.

4: Banks are capital constrained not reserve constrained

Number four gets down to the heart of the matter. Banks are not lending because they are capital constrained, not because of any reserve issues.

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) sets standards that pertain to asset quality and required capital that the banks must hold.

- International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards

- Minimal Capital Requirements

The first document is a whopping 284 pages long while the second is 150 pages long. I do not advise reading either. I include them for completeness.

Capital requirements

Wikipedia explains Capital Requirements and Capital Adequacy Ratio in brief form but the articles need work. Nonetheless, they seem to be a reasonable although complex overview.

From Wikipedia: The capital ratio is the percentage of a bank’s capital to its risk-weighted assets. Weights are defined by risk-sensitivity ratios whose calculation is dictated under the relevant Accord.

Here is a chart on risk weightings. Remember what happened to those AAA rated loans?

Risk Weightings

Fed Can Provide Liquidity Not Capital

Flashback March 01, 2008: Poole, Paulson, Bernanke on Bailouts and Bank Failures

Fed Governor William Poole on Moral Hazards:

I am more skeptical of the financial strength of the GSEs, and believe that we could see substantial problems in that sector. According to the S&P Case-Shiller home value data released earlier this week, as of December 2007 average prices had declined by 15 percent or more over the past 12 months in Phoenix, San Diego, Miami and Las Vegas. We can add Detroit to the danger list as the home price index for that city is down by almost 19 percent over the 24 months ending December 2007. With house prices falling significantly in a number of large markets, many prime mortgages issued a few years ago with a loan-to-value ratio of 80 percent may now have relatively little homeowner equity, which increases the probability of default and amount of loss in event of default.

As I have emphasized before, the Federal Reserve can deal with liquidity pressures but cannot deal with solvency issues. I do not have any information on the GSEs that the market does not also have. Nevertheless, in assessing the risk of further credit disruptions this year, I would put the GSEs at the top of my list of sources of potentially serious problems. If those problems were realized, they would be a direct result of moral hazard inherent in the current structure of the GSEs.

First Nationalized Bank Of Fannie

Poole hit the nail on the head. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac blew up and were nationalized. They did not run into reserve constraints. They ran smack up against capital constraints.

Also note that the Fed did not bail them out. Taxpayers did, authorized by Congress. The losses might hit $400 billion.

Fannie Mae is not a bank, but for all practical purposes it may as well be. Much lending growth comes from the GSEs. Money (credit really), is borrowed into existence, and redeposited elsewhere, and lent out over and over again.

When Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac ran into problems, capital was provided after the fact, not by the Fed but by taxpayers. The same applies to Citigroup, Bank of America, Wells Fargo on down the line.

In the March 2008 Poole post, I also commented on Bernanke.

Bernanke Expects Bank Failures

Testifying before Congress on Thursday, Bernanke stated Banks should seek more capital.

“Among the largest banks, the capital ratios remain good and I don’t anticipate any serious problems of that sort among the large, internationally active banks that make up a very substantial part of our banking system,” he said in response to a question during semi-annual congressional testimony.

“They have already sought something of the order of $75 billion of capital in the last quarter. I would like to see them get more,” Bernanke said.

“They have enough now certainly to remain solvent and remain … well above their minimum capital levels. But I am concerned that banks will be pulling back and not making new loans and providing the credit which is the lifeblood of the economy. In order to be able to do that … in some cases at least, they need to get more capital,” Bernanke added.

Bernanke certainly blew it about the large banks being well capitalized. However, he was certainly correct with “In order to be able to [lend] … in some cases at least, they need to get more capital”

Note that this was a capital concern not a reserve concern.

Capital Is The Problem At Virtually All Banks

Flash forward August 19, 2009: Emails from a Bank Owner regarding FDIC and Under-Capitalized Banks.

Here is an interesting followup email from ABO [a Bank Owner and CEO] regarding bank capital.

ABO Writes:

I talked to a friend this morning who is retired from both the Federal Reserve of Kansas City and RSM McGladrey. He now does consulting work with the FDIC, due diligence and other regulatory work. He said the picture he is seeing is worse than at any time in his life and CAPITAL is the problem with virtually all banks.

Inquiring minds will also be interested in an August 24, 2009 post Critically Under-Capitalized Banks Direct Result of “Wonderful Chain of Stupidity”. That post also shares some emails with “ABO” including …

Hiding The Losses

ABO Writes:

Take a look at how the FDIC is selling failed banks. It is a little different than in the past. The FDIC is using a loss sharing agreement that is usually around 80–20 and has certain guidelines on timing of the losses. I would guess that the losses on the failed banks are dragged into the future somewhat rather than being recognized at the time the bank is closed. This method would be less of an immediate hit to the fund and would probably create a contingent liability rather than a direct one. The banks that agree to this loss sharing plan are relying on the promise of the FDIC to make good on future guarantees for losses. The losses are not backed by the full faith of the government.

The Fed and FDIC always want to delay addressing the problems, hoping they will go away. Such structural problems seldom do.

Amazingly Financial Group was considered “well capitalized” right up to the brink of failure. When the bank did fail, the hit to FDIC was not immediately taken but stretched into the future.

The WSJ article notes ‘There are 1,400 banks that own mortgage-backed securities that aren’t backed by government-related entities such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.” What we don’t know is how many of those banks are levered up enough in garbage mortgages to fail.

Note too that those garbage trust-preferred securities problems are on top of the widely expected fallout from commercial real estate problems affecting small to medium-sized regional banks. Thus, banking woes are much deeper in many areas than either the FDIC or Fed is admitting.

FDIC Allows Banks To Hide Insufficient Capital

Let’s flash forward once again.

Dateline December 15, 2009: FDIC Approves Giving Banks Reprieve From Capital Requirements

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. gave banks including Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. a reprieve of at least six months from raising capital to support billions of dollars of securities the firms will be adding to their balance sheets.

Bank regulators including the FDIC and Federal Reserve want to permit a phase-in of capital requirements that rise starting next month under a change approved by the Financial Accounting Standards Board. The rule, passed in May, eliminates some off- balance-sheet trusts, forcing banks to put billions of dollars of assets and liabilities on their books.

Executives from Citigroup, JPMorgan, Bank of America, Wells Fargo & Co., Capital One Financial Corp. and the American Securitization Forum met FDIC officials Dec. 2 to discuss capital requirements related to the FASB measure.

The executives proposed that “the transition period should extend beyond 2010 to a point in the economy where unemployment is lower and issuers are less capital-restrained from growing their balance sheet and providing credit,” according to a paper the ASF presented the FDIC.

Citigroup suggested three years to offset assets and liabilities brought onto balance sheets, Chief Financial Officer John Gerspach said in an Oct. 15 letter to regulators. Requiring banks to “assume the risk-based capital effects immediately, or even over one year, is an undeniably severe penalty,” he wrote.

Fictional Capital

Not only are there no reserves, the above should prove without a doubt there is insufficient capital for banks to lend.

Amazingly, the Fed and banks have the gall to proclaim banks are well capitalized.

Global Implications Of Stronger Capital Rules From Basel

Just to prove capital is not just a US concern, please consider Japan Banks Fall on Stronger Capital Rules From Basel.

Global regulators have been wrestling with plans to tighten bank supervision following the worst economic crisis since World War II. The Basel Committee said yesterday banks’ core capital should exclude stock or instruments that may require lenders to make payments to third parties, as these could reduce reserves needed for meeting losses.

“The tightening of Tier 1 quality standards is overall negative for the Japanese banks because they have weak Tier 1 quality,” said Stephen Church, a research partner at Japaninvest KK, an independent research firm, in Tokyo. “The stock market is differentiating between those banks which have stronger Tier 1 and those which are weaker.”

The committee also said banks should have an “appropriate” period of time to replace such instruments.

Hopefully that proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that banks are capital restricted. Thus, even if banks had excess reserves (which they clearly don’t), banks would not be lending anyway.

Of course, the idea that banks need reserves in the first place is fallacious.

Let’s tie a bow on this five point package with …

5: Banks aren’t lending because there are few credit worthy borrowers worth the risk.

Even if banks had the capital to dramatically increase lending (which they don’t), banks would still have to make the determination they want to lend.

Backdrop Banks Face

- Yahoo! reports Credit card chargeoffs rise in November

- Bloomberg reports Seven U.S. Banks Are Seized, Raising Year’s Failure Toll to 140

- Bloomberg reports Banks Take Losses on Short Sales as Foreclosures Soar.

- Bloomberg reports ‘Shadow Inventory’ of U.S. Homes Climbs.

- Yahoo!Finance reports Commercial Real Estate Loans A Growing Problem For Banks

- CNNMoney Reports Bernanke: Weak recovery ahead

If you were a bank would you be anxious to lend into that? If you were a business would you want to expand into that?

Please consider the latest Fed Senior Loan Survey.

Demand for C&I loans from small firms

Lending Standards For Small Firms

85.5% of banks responding to the survey have lending standards that basically remained the same yet 44.6% of banks report moderately weaker demand for loans, with only 8.9% reporting moderately stronger demand for loans.

In spite of all the claims that banks are not willing to lend, the data suggests that the predominant factor is there are fewer businesses wanting loans.

Arguably (but there is no way to tell from the tables) fewer still credit worthy businesses want loans.

Those who want banks to increase lending, I have to ask “For What? To Who? At What Rate?”

There are actually plenty of reasons for banks not wanting such as rising unemployment, rising taxes, uncertainty over health care costs, proposed cap-and-trade costs, increasing consumer frugality, rampant overcapacity, and boomer demographics.

One Unaddressed Point

Gary North proposes Bernanke can force banks to lend. Really? When Bernanke knows banks are capital constrained? When it is obvious that it would be suicidal?

Bear in mind that Bernanke has recently talked about upping the interest on reserves, not making it negative. Moreover, by paying interest on reserves, the Fed can very slowly recapitalize banks over time while simultaneously and subtly suggesting that banks not take excess risks.

With that in mind, let’s try and stay within the solar system of 99.9% probability rather than the universe of theoretically possible negative 2% rates on reserves.

Excess Reserve Recap

1) Lending comes first and what little reserves there are (if any) come later.

2) There really are no excess reserves.

3) Not only are there no excess reserves, there are essentially no reserves to speak of at all. Indeed, bank reserves are completely “fictional”.

4) Banks are capital constrained not reserve constrained.

5) Banks aren’t lending because there are few credit worthy borrowers worth the risk.

Reserves? There are no reserves. Indeed, reserves are best thought of as negative. Instead, in cases of “too big to fail”, capital (not reserves), is supplied after the fact by taxpayers (not the Fed).

Thus, concern that excess reserves will lead to lending and inflation is totally unfounded in theory and practice.

Fractional Reserve Lending is really Fictional Reserve Lending. In practice, the major constraints to lending are insufficient capital and willingness of credit worthy borrowers to seek loans.