Ross Gittins has written a very good overview of the failings of neoclassical economics in today’s Sydney Morning Herald:

Self-righting markets and other shibboleths

The article mentions the Dahlem Report, but doesn’t provide a link to it. For those who would like to read it, here it is.

I also wrote a post on the Dahlem Report shortly after it was written, and helped publicise it by placing it on my blog. Given that its tone was in some ways even more dismissive of conventional economics than I am, the title for this post was obvious:

And you think I’m ornery? The Dahlem Report

There are, as Ross implies, many dissident groups within economics, but these are normally overshadowed–and crowded out of public commentary–by the dominant “neoclassical” school. As a result, most of the public takes what this school says to be all there is to “economics”.

Critics like Paul Ormerod, me, and many others have railed against this over the years–in public talks, in lectures to students in any subjects where we have some control over content, in books like my Debunking Economics or Paul’s Butterfly Economics–but we’ve largely been ignored by the public, since the economy seemed to be working just fine. Just as neoclassical economics said it always would.

And then along came the Global Financial Crisis.

A lot of the problems in neoclassical economics emanate from its methodology–the philosophy underpinning how neoclassical economists build models of the economy–and I cover this in a sample chapter from my Debunking Economics which is available online:

There is madness in their method

The key point that Gittins focuses upon is the obsession with equilibrium. To academics from other disciplines, this obsession appears quaint. Most sciences have concepts too, but they don’t attempt to model the systems at the heart of their discipline as if they are always in equilibrium. They have instead developed methods to analyse the behaviour of these systems when they are not in equilibrium–which is almost all the time (and when they do model equilbrium, their concepts of equilibrium are much broader than that which applies in neoclassical economics, which implies that all agents in the system are in a state of rest).

Instead, neoclassical economists reflect their isolation from the broad sweep of intellectual history by being ignorant of these very methods. I find this stunning–because the most basic such method is part of the education of any engineer, physicist, or mathematician, even if they only do an undergraduate degree in their subject and never become academics. This method is “Differential Equations”, and any engineer, physicist, or mathematician has to do at least an introductory course in these in order to get a Bachelors Degree.

Yet economists can graduate with PhDs without ever coming across them.

Many neoclassical economists think they know about these–after all, the core concepts in neoclassical economics concern things like “Marginal Cost” and “Marginal Revenue”, which are the differentials of “Total Cost” and “Total Revenue” with respect to output: “We don’t know about differential equations? Bah, what nonsense!”

In fact, differential equations are very different beasts from simple differentiation, since they consider the rate of change of variables not with respect to each other, but with respect to time (I’m tempted to provide a Wikipedia link to the concept of “time” for the benefit of any neoclassical readers who don’t know what it is… but I’ll restrain myself). They make it possible to model how the economy–or any other system–will behave when its not in equilibrium.

Instead, even Nobel Prize winners seem to believe that if they abandon the fantasy that the economy is in equilibrium, they will be unable to model its behaviour. Witness this statement from Paul Krugman on his blog when he gave some background to his recent critical essay on economics:

Actually, let me put it this way: the economy is a complex system of interacting individuals — and these individuals themselves are complex systems. Neoclassical economics radically oversimplifies both the individuals and the system — and gets a lot of mileage by doing that; I, for one, am not going to banish maximization-and-equilibrium from my toolbox [my emphasis]. But the temptation is always to keep on applying these extreme simplifications, even where the evidence clearly shows that they’re wrong. What economists have to do is learn to resist that temptation. But doing so will, inevitably, lead to a much messier, less pretty view.

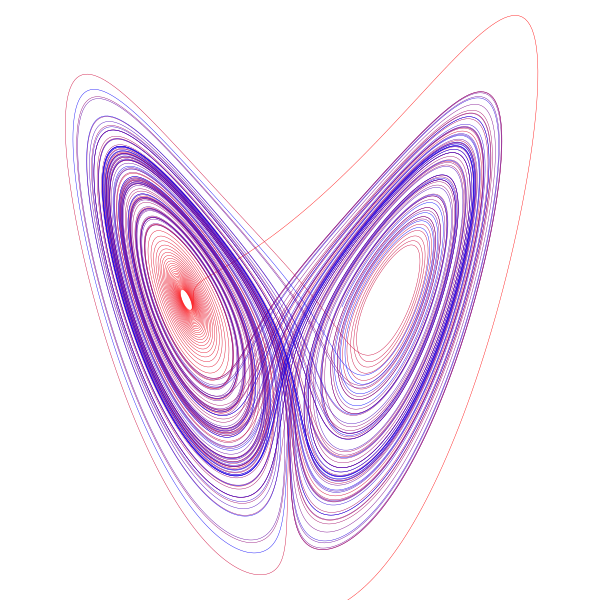

Then this guarantees you’re never going to understand complex systems Paul: the very starting point of complex systems analysis is the modelling of systems–such as the Lorenz Attractor that is the basis of meteorology–which are never in equilibrium.

Ironically, in that same essay Krugman notes that meteorology might be a valid model for economics to follow:

Third, on an interesting point raised by Discover (via Mark Thoma): won’t we eventually have a true theory that’s as beautiful as the full neoclassical version? Well, one thing’s for sure: we don’t have that beautiful final theory now, so the current choice is between ideas that are beautiful but wrong and a much messier hodgepodge. But my guess is that even in the long run it won’t be all that neat. Discover suggests general relativity versus Newtonian physics; but a better model may be meteorology, which as I understand it starts from some simple basic principles but is fiendishly complex in practice [my emphasis].

Well Paul, to understand meteorology, you’re going to have to give up on equilibrium–or rather on the fantasy that a complex system can be modelled as if it is in equilibrium. There are, for example, 3 equilibria in the Lorenz Attractor–all three of which are unstable. Equilibrium is a state in which the Attractor will never be.

I also find it remarkable that intelligent people like Krugman can be so ignorant of developments outside their own field of endeavour. Notice the comment he made that not applying the standard neoclassical economics simplifications like equilibrium “will, inevitably, lead to a much messier, less pretty view”.

I also find it remarkable that intelligent people like Krugman can be so ignorant of developments outside their own field of endeavour. Notice the comment he made that not applying the standard neoclassical economics simplifications like equilibrium “will, inevitably, lead to a much messier, less pretty view”.

Prettiness itself should not be an objective of science. But nonetheless, some of the prettiest objects in science are the result of non-equilibrium dynamics. The Lorenz Attractor is clearly one–take a look at it and you’ll see why people often talk of “the Butterfly Effect” when describing the instability of the weather. But there are many others.

I think my own non-equilibrium models of the economy have a similar beauty–here for example are two from my model of Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis. The first is of an economy without a government sector which undergoes a debt-driven Depression:

The fate is not pretty–the economy collapses as debt rises–but the image is “pretty”.

Both the image and the fate of the next model are pretty–this is an economy starting from the same initial conditions, but which has a government sector that practices counter-cyclical fiscal policy and therefore prevents a debt-induced crisis:

The above is the time path of employment and wages in this model, which is actually a 2D slice through the 4‑dimensions of the model: (1) the wages share of output; (2) the employment rate; (3) the debt to output ratio; and (4) government spending as a percentage of output). This next view shows 3 of those dimensions (excluding government spending), and the 2 dimensional view of the previous simulation is shown as a shadow below the 3D shape):

So the output of non-equilibrium models can be “pretty”–it’s just the picture they craft of capitalism that isn’t pretty. It isn’t a system that automatically reaches equilibrium and ensures the best outcome for the largest number of people. It may not be “pretty” in that way, but it is the world in which we live.

As Gittins argues in his piece, we have no choice but to understand that system, and the neoclassical obsession with equilibrium is possibly the major reason why we have not understood it to date.